As I’ve touched on before, the prime drivers of our economic system have become growth and efficiency, usually represented by GDP / GNP growth. The logic seems to make sense on the surface – more growth and more efficiency leads to more stuff being produced, more jobs, cheaper stuff all of which should lead to improved welfare, eventually, for all people on the planet. Unfortunately, it is becoming increasingly clear that this is not the case.

Some foresighted thinkers realized this as early as the ‘70s, when these global trends started to become clear. With the development of Systems Thinking techniques, pioneered by Jay Forrester at MIT, it became easier (though still very difficult) to better identify causal relationships in complex systems – such as the global macro-economy.

As a result, one of Forrester’s students, Donella Meadows co-authored Limits to Growth – a landmark work that unfortunately has so far failed to have a major impact on mainstream economic thinking – I’ll get to my thoughts on why in a minute.

Closely related is Herman Daly’s concept of a “steady state economy" – where progress, development, growth of value continue to drive the human endeavor, but physical growth of the economy – extracting more stuff and moving it around – reaches an optimum scale, an appropriate balance, a steady state… sustainability.

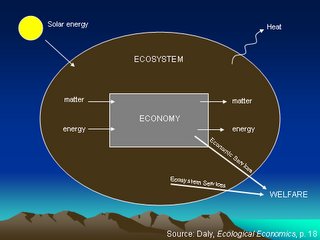

Central to this concept is a very simple differentiation between economic world views. The steady state world view can be represented as such:

The system boundaries are set by the biosphere, and the harsh reality that we only have one planet, which is a closed system – meaning there is transfer of energy across the boundary (sunlight in, and radiant heat out) but no movement of matter across the boundary (with the exception of insignificant movement in the form of satellites/spaceships out and asteroids in). Within that system of the biosphere, we’ve got society cranking along with all of its economic activity that takes resources from the earth’s crust and the biosphere and releases waste back into the biosphere.

These concepts are very closely related to understanding the System (Level 1) that we talk about in the 5-level framework, and the 4 Sustainability Principles (Level 2).

The old, yet still dominant world view is radically different. The economy is not considered in relation other realities – it is considered on its own with growth defining success. Natural resources are seen as inputs and outputs that drive the economy, and boundless growth is assumed to be possible and desirable:

When these economics models were developed they made perfect sense. For all intents and purposes, there were no limits to growth. The “economy” was so small in relation to abundant natural resources that any impact the ‘inputs and outputs’ had on natural systems was negligible to the point of insignificant.

One hundred years of growth and development has changed that. As we know, to say the impacts are now very significant is a gross understatement. So, what’s needed is a change in outlook and a revaluation of what our real goals are as a species. I think we can all agree that first and foremost, we’d like to survive – sustainability. That’s the baseline and to do it we need to shift the sum of our actions so that as a society we don’t violate the Sustainability Principles.

A good place to start is to re-evaluate the indicators we use to measure success. Right now that essentially means one very crude indicator – GDP / GNP. The basic components break down as follows: GDP = consumption (public & private) + investment + exports − imports

It’s very basic and simplistic, and I think if we were to ask most economists they’d concede that. Nevertheless it has become the definition of success for nations, due to the speed and complexity of our global economic system, which demands a simple gauge to measure “success”. The problem is that it measures physical growth (a huge problem in terms of sustainability as we saw through the world-view diagrams), it does not differentiate between desirable and destructive economic activity, and it only measures what is measurable.

Robert Kennedy (please suspend any political pre-conceptions you may have here) put it much more eloquently than I could:

The Gross National Product includes air pollution and advertising for cigarettes and ambulance to clear our highways of carnage. It counts special locks for our doors and jails for the people who break them. GNP includes the destruction of the redwoods and the death of Lake Superior . It grows with the production of napalm, missiles and nuclear warheads. And if GNP includes all this, there is much that it does not comprehend. It does not allow for the health of our families, the quality of their education or the joy of their play. It is indifferent to the decency of our factories and the safety of our streets alike. It does not include the beauty of our poetry, the strength of our marriages, the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. GNP measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country…”

Beyond that, a better understanding of Human Needs should help us evaluate what the aims of our economic endeavors and our resulting economic policy should look like.

So where does that leave us? Well, in addition to an understanding that our true goals are to ensure sustainability and meet human needs so we can live fulfilling lives without undermining future generations’ ability to do so, we should probably develop some better indicators. This has been done, and the results have been fascinating.

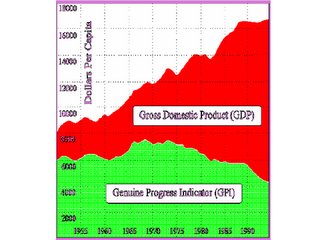

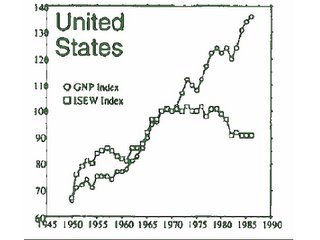

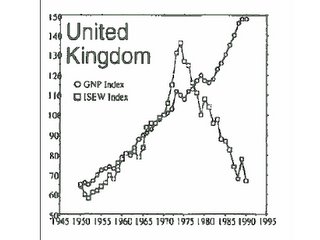

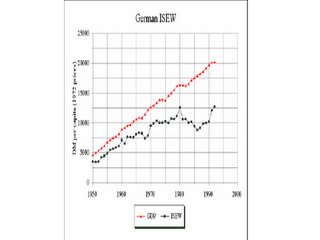

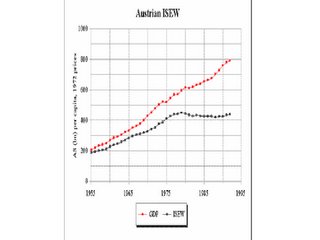

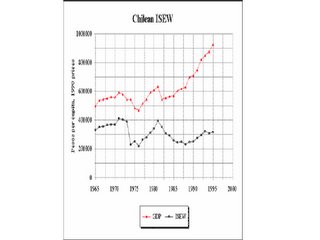

The Genuine Progress Indicator and the Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare are two of the better known attempts at developing more appropriate tools for measuring economic success. While their methodologies are different, they essentially work to subtract some of the negative economic endeavors we’re forced to engage in, instead of adding them on as if they were positive attributes to society. The concept is that there are costs as well as benefits and the costs should be subtracted, not added. The costs are things like costs of air, water and noise pollution, loss of wetlands and farmlands, cost of resource depletion, cost of family breakdown, cost of crime, etc.

When compared to GDP, some interesting conclusions can be drawn. The results may or may not be surprising to you depending on how you see the world. In most cases, these indicators clearly show that while GDP and a growth-focused model is an effective approach to development initially, there is a threshold point, where continued growth actually starts to result in a decrease in welfare.

THRESHOLD HYPOTHESIS:

“For every society there seems to be a period in which economic growth–conventionally understood and measured-brings about an improvement in the quality of life, but only up to a point-the threshold point-beyond which, if there is more economic growth, quality of life may begin to deteriorate.” (Max-Neef, Ecological Economics, 1995).

_

In most other industrialized nations the threshold appears to have been crossed a bit later – the in the late-‘70s or early-‘80s.

In addition to highlighting that GDP should not be the end-all-be-all that it has become, this threshold-hypothesis could illuminate some key aspects of our macro-economic system.

At the top of the list, it helps explain why the dominant growth oriented neo-classic economic model is so deeply entrenched, and why economists hold on to it so desperately - it worked.

This hypothesis seems to show that welfare increased right along with GDP before the threshold. In addition to the fact that it worked, economists have been hard at work to gain prominence in academia, to prove that the discipline is a science, with concrete laws, and ‘proven’ models to support them. There are slews of jokes about economists working hard to make reality fit the model instead of the other way around – but the consequences of this misguided perception of reality and the policy that springs from it is no laughing matter.

It’s important to remember the obvious here - that most economists are very smart people, and it’s not surprising that after spending huge chunks of their lives (and usually a lot of cash) learning and understanding the nitty gritty details of economic theory and how these models work (with plenty of historic proof that they do work well under certain circumstances) that there is a tendency to hold on to them. Because we’re dealing with complex systems it’s very easy to get lost in the leaves of blame, to write off negative impacts as unfortunate side-effects that are necessary to improve overall welfare, which will happen eventually if we just stick to the model.

Due to the over-specialization in universities and society as a whole, communication and understanding across disciplines is in rapid decline, and that is very dangerous when we get to dealing with the complex, interrelated ecological and social systems upon which our survival depends. I’m over-due for a post on transdisciplinarity on the subject…

But this post has already gotten way too long – it’s because exams are over, and break has begun – the joys of student living, we’re looking at 3 solid weeks of time for idleness and reflection. Hopefully I’ll get a lot of the reflections up on the blog, so stay tuned, and stay going…

3 comments:

How much better off we might have been If Robert K had survived.

How much better off we might have been If Robert K had survived.

johnny damon is evil. miss you. spraguey

Post a Comment